What is Your Definition of a Strategy?

Developing strategies is a fundamental part of successful strategic planning. With that in mind, I’ve always found it interesting that the question of “What is a strategy?” is rarely discussed when preparing for strategic planning. The word “strategy” is one of those words that we believe everyone understands what we’re talking about when it’s mentioned. My experience in facilitating strategic planning processes for over twenty years has been to the contrary.

When I teach my Essence of Strategy® workshop to groups of CEOs and leaders across the country, I begin the three-hour session by asking the question, “What is a strategy?” I ask the participants to write down their definitions. Here are a few definitions that I have received:

- “A strategy is a road map for getting where you want to go.”

- “A strategy is a plan of action designed to achieve a long-term goal or overall aim.”

- “A strategy is a series of actions undertaken by a company according to a particular situation.”

- “A strategy is a result of analyzing the present situation and changing it when-ever necessary.”

- “Strategies are the decisions that are required to achieve the company’s purpose.”

- “A strategy is a comprehensive plan to ensure that the objectives of the company are achieved.”

- “A strategy is a blueprint for how to build the company of your dreams.”

- “A strategy is a guideline for the organization to make decisions.”

This (admittedly unscientific) experiment never fails to reveal that no two definitions in any group are ever the same. Some of the participant’s definitions have similar language. Most, however, differ drastically from one another. Some definitions are detailed, while others are less than five words. Some speak to a high-level understanding. Others are much more tactical in their description.

My experiment’s consistent findings affirm my experience that those charged with strategic planning for their organization often don’t have a shared understanding or definition of a strategy. The result is that there are uncommunicated expectations and, more importantly, what they called a strategy may not be a strategy at all. Thus, this lack of a shared definition of a strategy has the potential to undermine the ability to gain alignment and commitment to strategy execution. This article examines common misunderstandings of a strategy and then suggests practical ways to leverage this information to improve your strategic planning and strategy execution efforts.

There are two often overlooked facts about a strategy that causes confusion when trying to get on the “same page” with your team or direct reports. The first area of confusion comes from two very distinct contexts of strategy in business. One context of strategy refers to the summation of an overall plan for achieving an organization’s mission and vision (i.e., an overarching strategy). The other context refers to the plan for achieving a specific objective within an overall plan (i.e., a strategic plan strategy). Failing to clarify which context of strategy you’re referring to will cause confusion in any conversation you’re having about strategy. This article focuses on the latter context of a strategy: a strategic plan strategy.

The second area of confusion about strategy stems from the context of a strategic plan strategy referenced above. That’s because, in practice, a strategy for one level of leadership may not be a strategy for another level of leadership. To put it another way, whether something is a strategy often depends on what leadership level is focused on it. For example, a CEO or an executive team’s strategy may become an objective for the Director level. The Director level will have to develop strategies to achieve the objectives they’ve been given. Director-level strategies will become objectives for the Manager level. And so it goes down the management line as the execution of a strategy cascades throughout the organization. In this way, everyone in the organization is working on a strategy in some way. This is one reason why it is beneficial to include everyone in the organization in some form of training on strategy development and execution.

Depending on your organization’s size and complexity, these distinctions can either seem like an exercise in semantics or can be part of the obstacle to gaining clarity about and commitment to the execution of specific strategies.

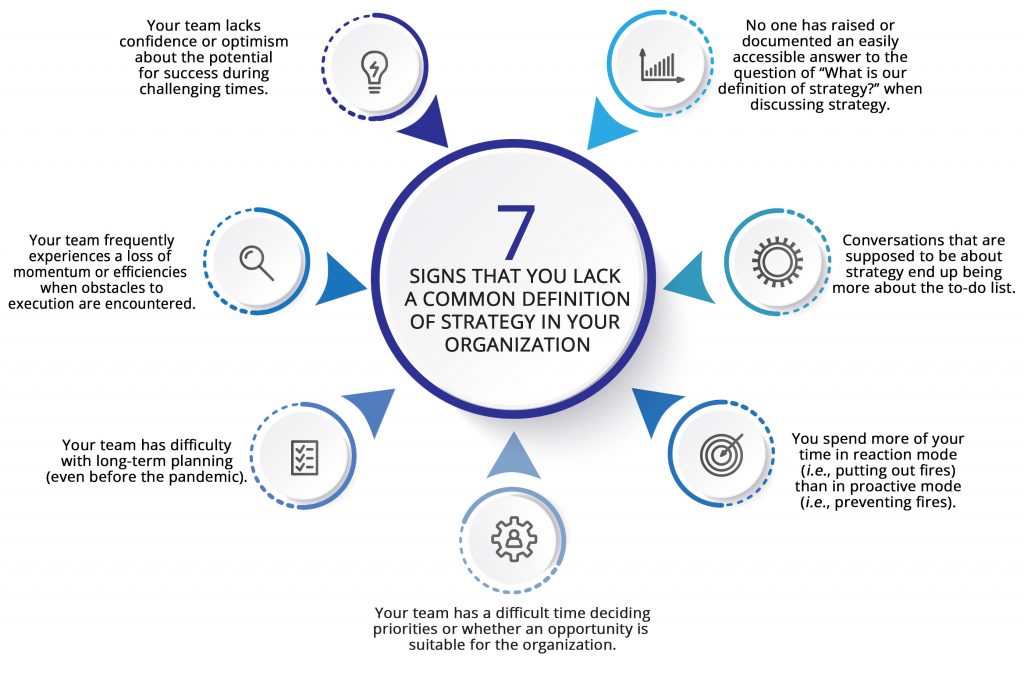

Leaders can be tempted to believe that their team shares the same definition of strategy, or if they don’t, their lack of a shared definition doesn’t cause any significant problems. These leaders are usually wrong on both accounts. They mistake silence for understanding rather than the confusion or apathy that it most often represents. A lack of clarity about the definition of a strategy can have a cascading effect and play a role in producing results that seem unrelated on the surface. How do you know if your organization is suffering from the effects of not having a common understanding or definition of a strategy? Here are seven warning signs that I’ve seen in my work.

- When discussing strategy, no one raises the question of “What is our definition of a strategy? or documents an easily accessible answer for future discussions.

- Conversations that are supposed to be about strategy end up being more about the to-do list.

- You spend more of your time in reaction mode (i.e., putting out fires) than in proactive mode (i.e., preventing fires).

- Your team has a difficult time deciding priorities or whether an opportunity is right for the organization.

- Your team has difficulty with long-term planning (even before the Covid-19 pandemic).

- Your team frequently experiences a loss of momentum or efficiencies when obstacles to execution are encountered.

- Your team experiences a lack of confidence or optimism about the potential for success of specific objectives or the organization’s future viability during challenging times.

There has never been a single and definite definition of strategy pertaining to business. The word “strategy” has its origin in war and military application, where it refers to methods to prevail over enemies. Since its origin, the term strategy has been applied in various contexts and disciplines, from political and economic to organizational development. The war reference is not lost in business as some still see developing a business strategy as an exercise in warfare. This varied evolution of the term strategy is another reason why clarity is needed about how the term will be used in your organization. Reaching for this level of clarity will begin the process of unifying conversations and decision-making. As you begin thinking about creating a unified definition of a strategy, it may be easier to start with what a strategy is not.

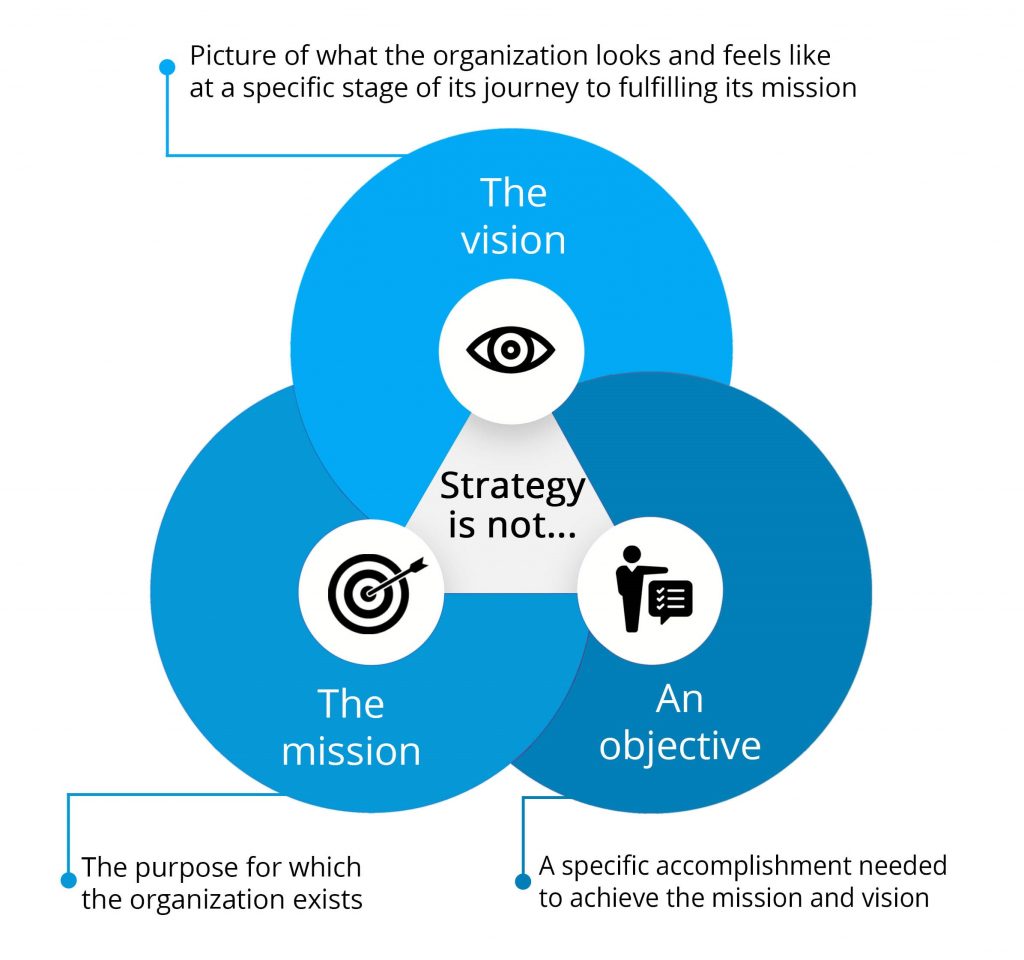

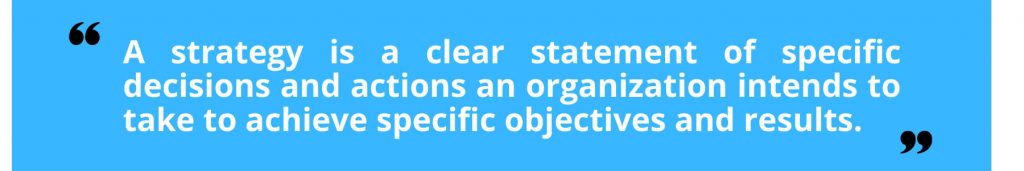

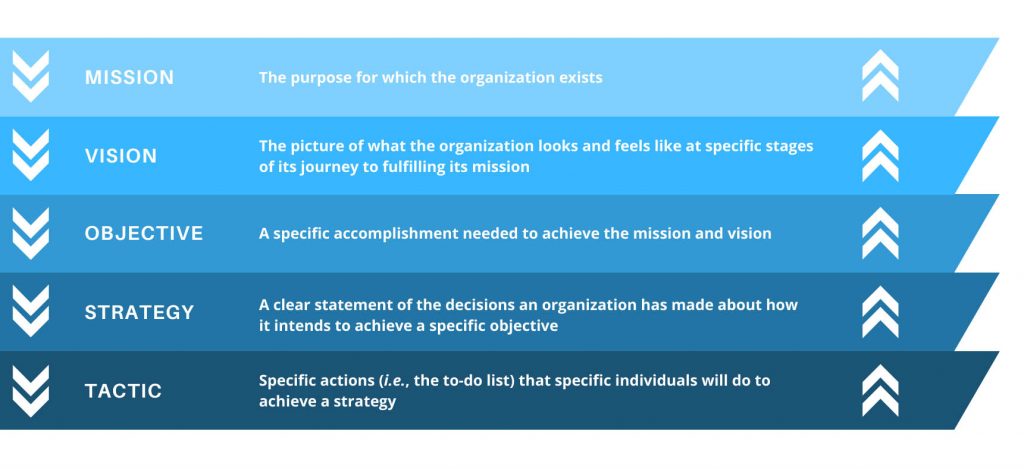

A strategy is not a mission. A mission is the purpose for which the organization exists. It’s the organization’s overarching “Why?” A strategy is not a vision. A vision is the picture of what the organization looks and feels like at a specific stage of its journey to fulfill its mission. Finally, a strategy is not an objective. An objective is a specific accomplishment needed to achieve the mission and vision. This is where a strategy comes in. A strategy speaks to how you plan to achieve a specific objective. Here’s my working definition of a basic strategy:

While my definition above is succinct and suffices for a general discussion, it provides no guidance for determining whether a strategy is actionable. (For this, I encourage you to read my article “What is an Actionable Strategy?”) Prematurely launching into executing a strategy before it becomes actionable is one of the primary reasons some strategies don’t receive the commitment or have the impact needed to achieve the intended objectives.

In my work as a Chief Strategy Officer and strategic planning facilitator, I often meet leaders who believe they are being strategic when they are merely being tactical. They are “in the weeds” more than they realize or care to admit. It will serve your strategy development efforts well to understand and distinguish strategies versus tactics.

Tactics are the specific things that end up on your “to-do” list. They are specific actions that increase the likelihood of achieving a strategy. The hierarchical order (from the bottom up) goes like this: a tactic supports the achievement of a strategy; a strategy supports the achievement of an objective; an objective supports the achievement of a vision; a vision supports the achievement of a mission; achievement of a mission fulfills a purpose. Here’s how I think about it: The mission and vision are the “Why.” An objective is the “what.” A strategy is the “how.” A tactic is the “will”… as in “will do.”

Having tactics (i.e., a to-do list) that are not based on actionable and integrated strategies is another reason why so many business owners and executives are frustrated and merely spinning their wheels. In other words, they may be busier than ever before and investing significant resources but not experiencing significant progress toward their objectives or achieving the expected return on their investment. Suppose this is where you are right now. In that case, I hope you will take proactive steps, such as those suggested in a later section of this article, to begin the process of ending the cycle of inefficiency and frustration in strategy execution.

If you’re thinking about creating a definition of strategy and refining your strategy development process as a result for your organization, do not fall prey to these seven myths:

Myth #1: A strategy is more likely to be achieved if it gets buy-in from key individuals in the organization.

Fact: Buy-in is not the same thing as commitment. Buy-in is in the head. Commitment is in the heart. Just because everyone either nods their head or verbalizes their agreement doesn’t mean that they are committed to a strategy’s success. Without commitment (i.e., a fully resolved dedication to do whatever is necessary to see it come to pass), a strategy’s success is always in jeopardy.

Myth #2: You should only focus on realistic strategies.

Fact: Having a so-called “realistic” strategy does not ensure success. Many well-known companies that no longer exist had realistic yet ineffective strategies. The strategies supporting Ray Anderson’s Mission Zero initiative at Interface Carpets are a great example of unrealistic strategies. Even key employees at Interface initially thought the strategies were impossible. Yet, they succeeded. I encourage you to read more about Ray Anderson and his Mission Zero journey.

Myth #3: There is a correlation between the time spent planning and the results.

Fact: Many believe it takes “quality” time to produce an effective strategy. There is no hard-and-fast rule about how much time you should spend developing a strategy. The amount of time it takes to create an actionable strategy depends on the framework and process you follow, how much preparation has been done before the planning meeting, the planning team’s experience and skill with developing strategy, the complexity of the objective, the time allotted to achieve the objective, the commitment and resolve of the team to achieve the objective, and the commitment and resolve of the team to use a framework to develop the strategy.

Myth #4: Once you have planned a strategy, stick with it.

Fact: No strategy should be written in stone. While a strategy should never be changed on a whim, it is important to remember that a strategy represents your best thinking with the information you had when you developed it. Therefore, as new information and new experiences inform your thinking, your strategies should be refined accordingly. This is one reason why I encourage all of my clients to have a rigorous strategy refinement process.

Myth #5: You should not develop a strategy until you’ve completed an exhaustive analysis of your market.

Fact: There is no such thing as exhaustive research or analysis. Effective research and analysis is an ongoing effort, which is one reason why strategic planning is an ongoing process. No matter how much research you do, there is always information you haven’t found or considered. While you were analyzing what you uncovered, new information was most likely being created. That’s why waiting until you have found or learned everything there is to know about a subject or situation would leave you with no time to develop or execute the strategy.

Myth #6: Spending significant time on strategy isn’t that helpful until your business reaches a specific size since it isn’t referred to daily.

Fact: Having an effective strategy that is documented is important no matter the stage of your business. Michael Porter addressed this point best when he said, “The company without a strategy is willing to try anything.” So, yes, certain aspects of a strategy are not referenced daily. However, a strategy is meant to guide day-to-day activities (i.e., the to-do list). In this way, a strategy is referred to daily, albeit not directly.

Myth #7: You don’t need help from the outside to develop your strategy.

Fact: You can not be a highly effective facilitator and participant at the same time. The objectivity and opportunity to observe all aspects of the process and engage all participants like a facilitator is compromised when you are the participant. The opportunity to focus and be fully immersed in the activities to think of effective solutions like a participant is compromised when you are the facilitator. In this way, having an objective, skilled and experienced facilitator with a vetted process will always add value to the strategy development process. With this understanding, it’s not a question of whether you need help. The real question is whether the investment in expert facilitation makes sense compared to the expected return on the strategy’s investment.

So, how do you use and benefit from the information in this article? Here are six steps that will get you going in the right direction.

- Document your answers to these two questions: (1) What does strategy mean to you? (2) What is your definition of a strategy?

- Make it a team exercise to develop a common, unified definition of a strategy for the organization. Collaboration begins the process of gaining commitment to a strategy’s execution.

- Dissect your definition of strategy to form a checklist of its components. These components comprise the litmus test that should be used going forward for what you call a strategy.

- Add your definition and checklist to your standard operating procedure for strategic planning. Refer to the last step if you don’t have an SOP for strategic planning or strategy refinement.

- If you have strategies that were written before creating your unified definition and checklist, then use your checklist to confirm that each of your written strategies adheres to the definition. Refine those that do not meet your new definition.

- If you want expert help in developing a useful definition of a strategy and a robust process for developing and executing your strategies, take one more step and contact our office. (info@icfstrategicplanning). We’re here to serve and would love to connect with you.

It is important to have a definition of a strategy to improve strategy execution. However, the specific definition you come up with is not as important as the need for everyone on your team to know and understand that definition. High-performing cultures have a common language and a shared understanding of specific words in that language. Developing a common definition of a strategy strengthens collaboration, builds trust, and lays the foundation for clear communication. These elements are needed to gain the commitment essential to increasing the likelihood of successful strategy execution. I encourage you to complete the suggested steps above to begin experiencing the power of having a common definition of a strategy for your organization.

Sherrin Ross Ingram is the Chief Executive Officer of the International Center for Strategic Planning, a management consulting firm specializing in scaling for aggressive growth companies. She oversees the development and support of strategic initiatives for client companies and is a trusted advisor and coach to growth-focused CEOs and leadership teams. She is also an Independent Corporate Board Director, an attorney, best-selling author, and a Master Strategic Planning Facilitator for companies in need of a proven process for updating strategic plans, developing new strategies to leverage new opportunities, or restructuring to increase competitive advantage.

Sherrin provides valuable perspectives to boards and executive teams that improve strategy execution and maintain a balanced drive for growth and fiscal responsibility. In addition, she is a frequent keynote speaker on strategy development and leadership topics at business meetings and conferences around the world. Learn more about her work at https://www.sherrin.com.

Sign up for Sherrin’s Strategies & Tactics Monthly Report

to get insights and advice to improve strategy execution, and

get the printable PDF version of this popular article as a free gift!